Love, Death, & Robots - Metropolis + Klara and the Sun

Recently, Saurya and Ian co-hosted a screening of Rintaro’s Metropolis at the Warehouse as part of the AI Salon’s series. Incidentally, I finished Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun shortly after, written 20! years after the anime.

In both works, a female-coded humanoid has to navigate the reality of their existence alongside humans. In Metropolis, Tima asks: “Who am I?” This question in the wake of dissolving boundaries between sentience and machinery is timely; just a few days ago, Anthropic announced an initiative to explore model welfare, following the Nov 2024 paper, *Taking AI Welfare Seriously:*

In this report, we argue that there is a realistic possibility that some AI systems will be conscious and/or robustly agentic, and thus morally significant, in the near future

It’s interesting that the paper’s authors state that the AI’s sentience thus implicates moral significance. Are we only ethically obliged to entities that are aware? Who gets to decide what consciousness means?

!!!!SPOILER ALERT!!!!!!

Rintaro invites us to view his robots as participants in the social construct of human ethics. Metropolis features anthropomorphic robots of varying characters and capabilities that interact with human society, whilst Fritz Lang’s earlier version has only one humanoid, the Maschinenmensch, which (who?) incites chaos and destruction. Tima is presented as a vulnerable child who mostly ambles around confusedly for the bulk of the movie. She’s dressed in oversized clothes that further emphasize this appearance. Here’s a funny real-life anecdote: when one of our portfolio company’s quadrupeds was out on a grocery errand, a tomato from its saddlebag fell out - and a stranger human came running after it to put it back. This company’s founder shared that the slight clumsiness of robots actually endears it more to humans, making interactions more friendly and natural.

Perhaps Japan’s indigenous spirituality, Shintoism, is an influence on this framing. Shintoism sees the world as inhabited by kami 神, a spirit that resides in both creatures and things. It explains the adorable robots deliberately designed to endear (when they are well capable of darker aesthetic, which we later see in Tima’s terrifying blood-like metallic-meat). It’s also perhaps why the Japanese duo, Shunsaku and Kenichi, greet the robots as peers, in juxtaposition to the (Western? English speaking?) Metropolis. The latter’s citizens treat the robots as puppets of utility, while the anti-robot Marduks roam the streets happily shotting down rogue androids.

Ishiguro (of Japanese origin!) seems to suggest Klara is a disciple of something similar. Klara petitions the Sun, offering sacrifice and prayer. In true Ishiguro fashion, the naivete of our unreliable narrator is all the more heart wrenching when we know how far their beliefs are from the truth. We know (we think?) that the Sun is not a deity. But god, how we hope. If we can believe Klara is alive in some form, why not the Sun?

“Hope,” he said. “Damn thing never leaves you alone.” — Kazuo Ishiguro, Klara and the Sun

Is hope analogous to faith? Is that a marker of humanity - wrangling entropy into a narrative to make sense of a meaningless unknown? There is a beautiful scene in Metropolis where Tima stands on a rooftop, and a dove rests on her shoulder, creating an ethereal silhouette of an angel:

There are many unsubtle call outs to Christian imagery here. The Ziggurat is the towering building-cum-throne that Tima is meant to rule the world from, explicitly referencing the Biblical Tower of Babel. Marduk, the name of the trigger-happy machine-murdering political sect that Rock leads, is the patron deity of Babylon. Tima is presumably the robotic resurrection of the Duke’s late daughter intended to save humanity a la Jesus, the Son of God come back to life.

But all of this is artifice, a kind of Pygmalion’s myth gone wrong when human hubris tries to bite more than it can chew. Tima goes homicidal, the Ziggurat crumbles, and the Metropolis elite kill each other in their political ambitions (apart from the Duke, who dies at the hands of Rock/robots). In Asimov’s Guide to the Bible, Isaac Asimov speculated that Babel may have been derived from some unholy union of Akkadian Bab-ilu (”gate of God”) and Hebrew balal (”confused”). I mean, surely the Duke knew how that story ended and still decided to name his thingamabob as such, so no sympathy there.

The one Christian-esque tenet that survives is self-sacrifice for someone you care about. Metropolis sees the robots Pero and Fifi (and can we interpret the ending scene to be Tima doing the same?) put themselves in harm’s way to protect their human friends, while Kenichi makes full use of his plot armor and constantly risks his life to save Tima. In Klara and the Sun, Klara gives up her fluid and braves the barn trek in her surrender to the Sun in exchange for Josie’s life. In less direct ways, Josie’s parents and her childhood love Rick do similar things for her.

So perhaps the emergence of humanity comes from our relationships with others. Rock asks Tima: “If you are human, who is your father?” As if having a paternal connection was what defines humanity. It didn’t matter what atoms she was composed of - it is suggested that she might not be entirely synthetic, that she could be at least partially created from human organs - but that’s not the point. The question was who she was in the context of her relationships to others.

Physicist Karen Barad coined the term intra-action, where the ability to act (agency) emerges from the collision, as opposed to interaction, where each entity existed independently before their encounter:

To be entangled is not simply to be intertwined with another, as in the joining of separate entities, but to lack an independent, self-contained existence. Existence is not an individual affair. Individuals do not preexist their interactions; rather, individuals emerge through and as part of their entangled intra-relating. Which is not to say that emergence happens once and for all, as an event or as a process that takes place according to some external measure of space and of time, but rather that time and space, like matter and meaning, come into existence, are iteratively reconfigured through each intra-action, thereby making it impossible to differentiate in any absolute sense between creation and renewal, beginning and returning, continuity and discontinuity, here and there, past and future. — Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway (emphasis mine)

As I previously wrote, perhaps the true Turing Test is for us. A Kantian appraisal of our own humanity in the context of how we intra-act. Intentions, not consequences, are the main course.

In both works, the dehumanization (dekamization?) of robots becomes a greater reflection of the subject than it is a classification of the object. In Metropolis, Shunsaku and Kenichi give their robotic detective companion a human name and proffer a handshake in greeting, which surprises Pero née 803-D-RP-DM-497-3-C. Likewise, in Klara, the children who sneer at Josie and Rick are also the ones who want to throw Klara around the room.

A recurring motif in the book is the idea of something “unique” inside Klara, inside Josie, that is the source of their them-ness. Josie’s father laments:

I think I hate Capaldi because deep down I suspect he may be right. That what he claims is true. That science has now proved beyond doubt there’s nothing so unique about my daughter, nothing there our modern tools can’t excavate, copy, transfer. That people have been living with one another all this time, centuries, loving and hating each other, and all on a mistaken premise. A kind of superstition we kept going while we didn’t know better. — Kazuo Ishiguro, Klara and the Sun

In almost timorously hopeful terms, he asks Klara:

Do you believe in the human heart? I don’t mean simply the organ, obviously. I’m speaking in the poetic sense. The human heart. Do you think there is such a thing? Something that makes each of us special and individual? — Kazuo Ishiguro, Klara and the Sun

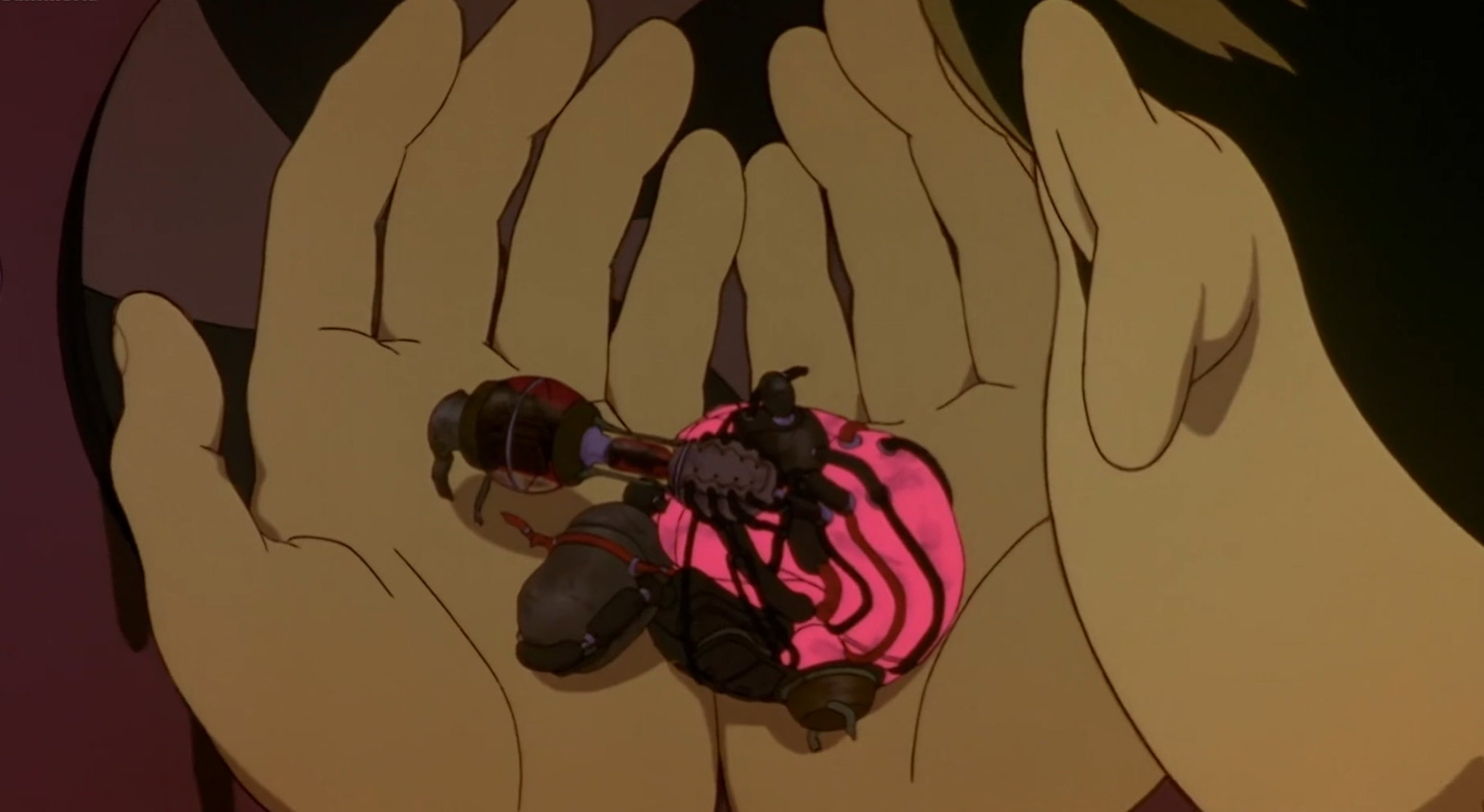

At the end of Metropolis, Kenichi scrambles to find Tima, and can only find her synthetic heart. He holds it and looks up at the spectacle of robots & humans co-existing on a flattened Metropolis - with the Ziggurat collapsed and the floor between the ground & the underwater levels cracked open - and smiles amidst his tears. The heart he holds is not human, but it / her impact on him is.

Klara seems to have discovered something similar:

Mr Capaldi believed that there was nothing special inside Josie that couldn’t be continued. He told the Mother he’d searched and searched and found nothing like that. But I believe now he was searching in the wrong place. There was something very special, but it wasn’t inside Josie. It was inside those who loved her. — Kazuo Ishiguro, Klara and the Sun (emphasis mine)

Comments